The Mongol Conquest and Its Cultural Impact (1271-1279)

The advent of the 元朝 dynasty in 1271 marks a decisive turning point in Chinese history. When Kublai Khan proclaimed the Yuan Empire after his victory over the 南宋 (Southern Song), he imposed the first foreign regime to govern all of China. The suicide of Emperor 赵昺 in 1279 symbolizes the brutal end of the Chinese imperial tradition, triggering an identity crisis among Confucian scholars.

The suppression of the Song Imperial Painting Academy created an unprecedented institutional void. Only 5% of official artists agreed to serve the new Mongol administration, according to contemporary records. This massive rejection can be explained by the caste system imposed by the Yuan, which placed the Han Chinese (汉人 ) in third position, behind the Mongols and the Semu.

Intellectual Resistance and Its Artistic Manifestations

Faced with this foreign domination, two artistic currents emerged:

The Tang Revival of Pro-Court Artists

Influenced by Mongol tastes for opulence, painters like 任仁发 revitalized the Tang style with vibrant colors and monumental compositions. Their works celebrate equestrian power and court scenes, reflecting the nomadic aesthetic of the new masters of China.

The Individualism of Retired Scholars

Refusing any collaboration, the majority of artists withdrew to Jiangnan, developing 文人画 (scholar painting). This movement drew its inspiration from the landscapes of the Five Dynasties and the Northern Song, but with a radically new personal expressiveness. The brush became an instrument of passive resistance.

The Four Founding Masters: Pillars of Cultural Resistance

These artists embody the quintessence of the Yuan spirit, merging poetry, calligraphy, and painting into what will be called the 三绝 (three perfections). Their refusal to serve the Mongols led them to create a coded visual language where landscapes became political manifestos.

| Artist | Major Contribution | Emblematic Work |

|---|---|---|

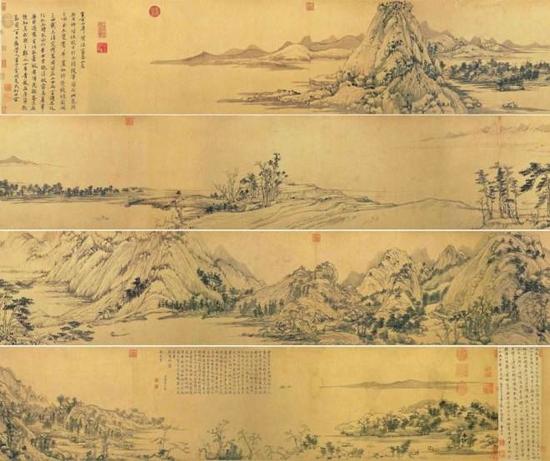

| 黄公望 | Inventor of the "dry landscape" with superimposed ink washes | 富春山居图 (Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains) |

| 吴镇 | Master of the solitary bamboo symbolizing resilience | 墨竹谱 (Ink Bamboo Album) |

| 倪瓒 | Pioneer of the minimalist compositions "an empty corner" | 容膝斋图 (Pavilion of the Bent Knee) |

| 王蒙 | Inventor of the "hemp fiber weaving" | 青卞隐居图 (Retreat in the Qingbian Mountain) |

富春山居图 - Monumental scroll of 6 meters created between 1347-1350, considered the "Holy Mountain" of Chinese painting

The Aesthetic Revolution of the Retired Scholars

Their practice of 写意 (idea painting) breaks with the realism of the Song:

- Use of monochrome ink as a metaphysical language

- Negative space as a spiritual dimension

- Calligraphy integrated into the pictorial composition

- Depopulated scenes expressing political desolation

This approach will durably influence Chinese art, as noted by the theorist 董其昌 under the Ming: "Without the innovations of the Yuan, our brush would have remained a prisoner of appearances."

Other Major Figures of the Yuan Era

赵孟頫 (1254-1322)

Controversial figure who served the Yuan while preserving the Song tradition. His famous 鹊华秋色图 (Autumn Colors on Que and Hua Mountains) established the model of the nostalgic landscape.

牧溪 (1210?-1269?)

Buddhist monk whose minimalist style influenced Japanese Zen art. His 六柿图 (Six Persimmons) remains a masterpiece of meditative simplicity.

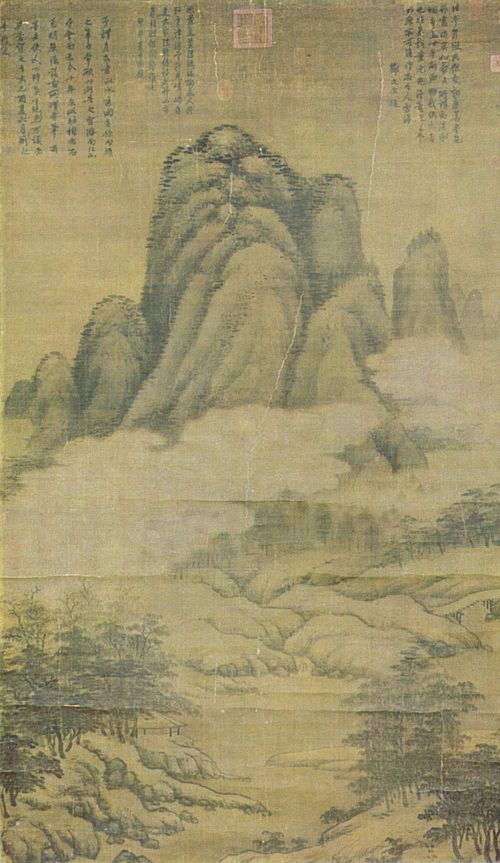

高克恭 (1248-1310)

Unique fusion of Chinese techniques and Central Asian motifs. His scrolls 云横秀岭图 (Clouds Crossing Beautiful Mountains) revolutionized the representation of cloud masses.

任仁发 (1254-1327)

Horse specialist appreciated by the court, his 二马图 (Two Horses) is a political allegory comparing honest and corrupt officials.

The Paradoxical Legacy of the Yuan

Despite its brief duration (less than a century), the Yuan dynasty leaves an indelible mark:

- Invention of the 册页 (leaf-through album) intimate format favoring experimentation

- Development of the 提拔 (colophon) transforming painting into an intergenerational dialogue

- Spread of pictorial techniques to Central Asia via the Pax Mongolica

- Emergence of the private art market compensating for the disappearance of imperial patronage

As summarized by historian 柯律格 (Craig Clunas): "The 'Yuan crisis' forced Chinese art to reinvent itself, giving birth to its most accomplished form." This period of foreign domination paradoxically liberated creation from academic canons, preparing for the flourishing of the Ming.

Tips for Appreciating Yuan Art

- Observe the variations of ink revealing emotion

- Decipher the integrated poetic inscriptions

- Identify the symbolic motifs (bamboo = integrity)

- Contemplate the empty space as an active element