Kungfu, WuShu, Chinese Martial Arts

Kung-fu (in Mandarin Chinese 功夫 ) is a generic term that expresses high mastery in a field. Kung is the depth of an art, its highest expression. One can therefore have the Kung-fu of calligraphy, poetry, painting, or even cooking.

Since the "Bruce Lee" Kung-Fu fashion, all styles of Chinese boxing are commonly called Kung-fu.

The term Wu Shu 武术 literally designates martial arts. It is used very commonly today and rightly so, as it has existed since antiquity. It should be noted that from 1928 to 1949, it was replaced by the term Guo Shu 国术 (national art). The term Wu Shu would therefore return after 1949 with the creation of "modern Wu Shu" (modern gymnastic form of ancient martial art).

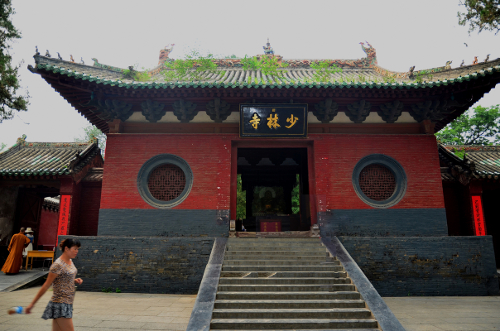

Henan Monastery

Legend has it that Wu Shu was born at the Shaolin Temple in Henan Province, north of China. This small temple (originally) was built in 464 to spread Theravada Buddhism (Great Vehicle).

Wu Shu developed there following the arrival of Da Mo (Bodhidharma). He seemed to have been a prince of a warrior caste of Brahmins who practiced combat techniques.

He would have come from India to meet Emperor Wu Di during the Liang Dynasty (502-557). Following the bad turn that the audience with the emperor took, he would have taken refuge in the Shaolin Temple. Upon his arrival, he would have found the monks in deplorable physical condition and taught them movements based on animals as gymnastics.

These movements would have given the basis for Shaolin martial arts. He would then have gone to meditate for 9 years facing a wall in a cave. From this retreat, the Chan Buddhist sect (Zen) meditative current was born.

A legend about him says that one day, during a meditation session, he fell asleep. Waking up, furious at having fallen asleep, he would have cut off his eyelids and thrown them to the ground. They gave birth to the first tea tree in China…

The temple gained its titles of nobility when thirteen monks saved the life of Emperor Li Shimin of the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

Today, Shaolin is considered the cradle of Chinese martial arts, and a Chinese proverb claims on this subject: "All martial arts under the sky were born in Shaolin." This hypothesis is, moreover, refuted by certain texts prior to the creation of the monastery.

Southern Shaolin

There was not only one Shaolin monastery in China. The one in the north is the most famous, but there may have been up to three in the south.

1- Putian Monastery

The first would have been located in the village of Lin Shan, on Mount Julian, not far from the city of Putian, Fujian Province. Built in 557 under the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589), it was destroyed during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi (Qing Dynasty 1644-1912).

2- Quanzhou Monastery

The second is the monastery located on Dong Yue Mountain, on the outskirts of the city of Quanzhou, Fujian Province. It was built in 611 under the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Destroyed three times, in 907 (Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907-960), 1236 (Southern Song Dynasty 1127-1279), and finally in 1763 on the order of Emperor Qian Long (Qing Dynasty 1644-1912).

3- Fuqing Monastery

Finally, the third is located on Shi Tzu Mountain, not far from the city of Fuqing, Fujian Province. It was probably built during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Information about it is scarce.

Thinking that all southern kungfu styles would have descended from the Shaolin of Henan, given the size of China and the enormous technical difference, is a heresy.

The Different Styles

More seriously, China lists several hundred different Kungfu styles. Some are family styles, others religious, sects, or clans.

Don't they say: ‘‘There are as many styles of boxing in China as there are coins in the pocket of a rich merchant.’’

They are classified by Northern Wu Shu style and Southern style. A saying goes: ‘‘legs in the north, hands in the south’’ even if in practice, this is not really the case…

They are also cataloged as internal style (neikong 内功 ) and external (waikong 外功 ). External styles would be based on physical strength and internal styles on breathing. But there too, in practice, there is often no distinction made…

China lists 56 different ethnicities. Some of these peoples have developed very good combat systems. Among these, the Hakka and Hui ethnicities stand out.

The Hakka people are a nomadic people. Their Wushu is distinguished by leg positions close together, allowing them to remain well stable on the ground. Their ways of working are easily recognizable since they generate force via a movement of the back in an arc and make a point of protecting the central line.

They created very famous boxes such as Long Ying (boxing in the form of the dragon), Jook Lam Tong Long (boxing of the praying mantis of the bamboo forest) to name but a few.

The Hui ethnic group comes from the provinces of Ningxia and Gansu. The Hui are Han converted to Islam.

They developed certain well-known boxes such as Cha Quan, Hua Quan, Hong Quan, or Xin Yi Liu He Quan (boxing of the heart and mind of the six coordinations).

There are enormous differences between the styles of Wushu. Some like to project the opponent by seizures, others long-distance combat, and still others close combat. There are several distances and, of course, several strategies.

Some Northern styles:

- Chang quan: long fist

- Cha quan: Muslim boxing of the Hui ethnicity

- Hong quan: red boxing

- Mizong quan: boxing of the lost trace

- Liu he quan: boxing of the six coordinations

- San huang pao chui: boxing of the three sovereigns' cannon

- Fanzi quan: spinning boxing

- Baji quan: boxing of the 8 extremes

- Tang lang quan: boxing of the praying mantis

- Mian zhang: cotton palm

- Ying zhao: eagle claw

- Hua Jia Men: the gate of the Fa family

Some Southern styles: (described here in the Cantonese dialect better suited to their origin)

- Pak mei: boxing of the white eyebrow monk

- Long ying: boxing of the dragon

- Hung gar: boxing of the Hung family

- Lee, Choy, Mok, Lau: boxing of the Lee, Choy, Mok, Lau families…

- Wing chun: boxing of wing chun

- Chow gar: southern praying mantis

- Ark fu moon: boxing of the black tiger

- Um ying kune: boxing of the five animals

- Fu zhao pai: boxing of the tiger claws

- Ngo cho kuen: boxing of the five ancestors

- Pak hok kune: boxing of the white crane…

Some internal styles:

- Taiji Quan: the boxing of the supreme ultimate

- Bagua Zhang: the palm of the eight trigrams

- Xing Yi Quan: the boxing of the heart and mind

- Liu He Ba Fa: 6 principles, 8 coordinations

- Neijia Quan: internal boxing of Siming Shan

It is not uncommon for a boxing style to fall into two categories at the same time. One can cite, for example, the Choy Lay Fat, which is a North/South style since it is a synthesis of three boxes, or the Pak Mei, which is itself an internal/external style…

Most boxes often also have several branches, depending on the masters of the descending lineages such as the Pak Mei of Hong Kong, and that of Foshan, or the Taiji Quan, style Yang, Chen, Wu, Wu Hao, Sun, Zhao bao…

Some styles are usually worked coupled with another "cousin" style. Baji Quan is worked with Pigua and can be coupled with Fanzi Quan or Tong Bei. Similarly, internal styles such as Da Sheng Quan with Xin Yi Quan or Pak Mei with Long Ying.

And finally, it is not uncommon for very different styles to bear the same name, for example, Hong Quan and Hung Gar, the first is a northern boxing style and the second is southern, or Chow Gar which is a family name and two styles bear the name; the southern praying mantis, and the boxing of the Chow family…

In short, enough to get lost, and that's why we talk about the forest of styles…

Written by Sifu Jonathan Barbary.

European Representative of Master Lao Wei Kei for Fatsan Pakmei Kune (Foshan Baimei quan)

Contact: https://www.jianghumartialscholars.com/fr-formulaire-de-contact

Website: https://www.jianghumartialscholars.com